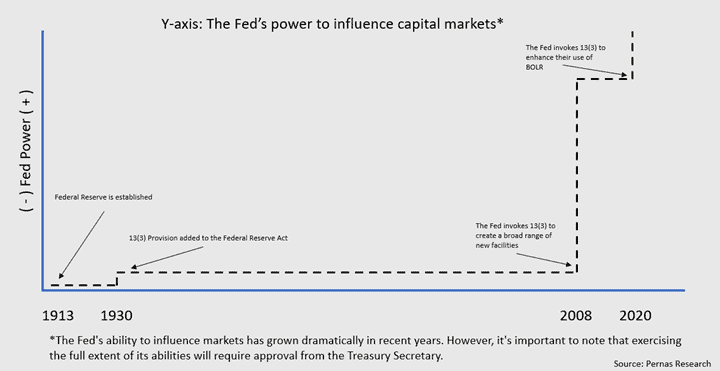

Since its inception in 1913, the Federal Reserve has had the ultimate responsibility of functioning as a Lender of Last Resort (LOLR). Since then, this LOLR function, along with the rest of the Fed's toolkit, has undergone a quantum leap in evolution (see conceptual illustration below). Furthermore, functions that have traditionally not been associated with the Fed, like Buyer of Last Resort (BOLR), have been implemented but to our knowledge practical attempts to educate market participants on the differences between the two has been lacking.

The Fed's actions, whether directly or indirectly, can provide a liquidity backstop to risk assets1 during periods of financial duress. A lack of a full understanding of the intent and administration behind Fed actions can cause investors to miss opportunities when allocating their capital. In this discussion, we will review:

- LOLR refresher

- The evolution of LOLR

- How the 13(3) provision ushered in BOLR

- Classification of Fed facilities into LOLR vs BOLR

- Implications of these expanded Fed functions

Lender of Last Resort (LOLR)

Why does this function exist?

Prior to the establishment of the Fed (and later deposit insurance), the history of the U.S. was marked by bank panics. The panic of 1907 was the last straw and led to the ratification of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. Allowing the Fed to act as LOLR was a way to restore confidence in the financial system when it was most needed. Banks can be fragile institutions, even those with pristine balance sheets, rock-solid underwriting, and ethical management teams are susceptible to runs. This is because banks are fundamentally engaged in the business of fractional reserve lending and maturity transformation. Banks take in deposits, which are short-term liabilities, and lend out most of these deposits as long-term assets. The bank can only function if depositors have confidence that their deposits will be available to them on demand. If depositor confidence declines, for whatever reason, banks cannot easily liquidate their assets to meet their short-term liabilities. Runs by depositors beget more runs and, in these situations, banks will need a "bank of banks" to extend emergency liquidity after exhausting other funding options. The Fed's LOLR function exists to serve this exact purpose and is critical to supporting our banking system.

Discount window

Any solvent depository institution in need of emergency liquidity can turn to the Fed's discount window. Banks must post collateral with the Fed, and the Fed extends short-term liquidity at a rate slightly higher than the Fed Funds rate (although the Fed can adjust this rate and term if needed). The discount window has undergone several enhancements to mitigate the stigma associated with discount window lending. Despite the Fed not reporting borrower details in real-time, banks fear that their activity at the discount window will be discerned by the market. Since borrowing from the discount window is a last resort, depositors and bank counterparties may lose confidence in the bank and withdraw their activities. Because of this stigma, the discount window is less effective than it could be, and attempts to improve this have had little success.

During the GFC, the St Louis Fed noted that "as concerns about bank conditions increased over the course of the financial crisis, the problems associated with stigma may have intensified. This likely resulted in significantly more stress in the interbank funding markets and tighter financial conditions than might have existed otherwise, in addition to more financial contagion."

The Fed created a better solution in December 2007 with the introduction of the Term Auction Facility (TAF), which allocated funds through auctioning and involved multiple participating institutions. This solved the stigma associated with the discount window and proved to be an effective solution to mitigate broad-based stress in the banking system. Although idiosyncratic issues that arise in the future will still see banks heading to the discount window, if the distress becomes widespread the Fed can quickly create funding programs to address the issue. For instance, the Fed created the Bank Term Fund Lending Program (BTFP2) in 2023 to address regional banking liquidity needs. Both TAF and BTFP are modern species of traditional discount window lending and fall under the Fed’s LOLR functions.

Beyond the discount window

While there have been improvements in how the discount window functions are administered, the function is essentially unchanged in spirit since 1913. What has changed is the financial system has outgrown the banking system. Most lending (and debt) is now being extended (and held) outside of depository institutions. New financial innovations like securitization have enabled a majority of credit to be held outside the traditional banking system. According to the Fed’s data, in 1980, 69% of the US credit market was held by banks, but by 2008, it was only 36%. These non-traditional lenders act in many of the same ways as banks, but without any formal regulatory support. Investment banks, money market funds, mortgage lenders, and other intermediaries all fall under the popular term "shadow banking" (which we use regrettably, as there is nothing sinister or disreputable about these actors).

Since the shadow banking system had not experienced a collective crisis, regulators had not seriously considered how to regulate it. Regulation tends to move slowly and is constructed with a backward-looking lens. It is difficult to provoke policymakers to agree to fix something unless the problem has already surfaced. Our political system is an apparatus that is sustained by garnering credit from the public. Unfortunately, policymakers are almost never extended credit when they are busy fixing the unseen problems of tomorrow. Only when the Great Financial Crisis began to painfully reveal that these shadow banks are essential pillars of the modern financial system did the Fed scramble to find ways to support it. This led to the invocation of a then-obscure 13(3) provision.

Lending to non-banks and the 13(3) Provision

Shortly after the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, it was amended to allow the Fed to lend money to non-banks under exigent circumstances. This …