Dear management teams and board members,

We want to address a problem that has gone largely unacknowledged in capital markets conversations: The widespread prevalence of buybacks and their potential to erode ongoing shareholder value. It is almost universally accepted that buybacks are a way of “returning value to shareholders.” While intelligent buyback strategies do indeed benefit ongoing shareholders, poor buyback strategies are far more common and have the opposite effect. They destroy shareholder value. This predicament arises because most management teams lack a systematic approach to assess the true value of their company's stock. Surveys conducted spanning the last four decades reveal that 55-80 percent of CFOs believe their company's stock is undervalued, while 20-45 percent consider it fairly valued, with only a fraction acknowledging overvaluation.1 Consequently, regardless of how high their company's stock price soars, it is always deemed an appropriate time for a buyback. Ironically, when stock prices experience significant declines and a greater percentage of stocks trade below fair value—a favorable environment for considering buybacks—such initiatives swiftly dwindle. This epitomizes the "buy high, sell low" behavior that characterizes contemporary buyback practices.

In this discussion, we will explore the following key points:

- The Evolution of Buybacks and Their Primary Drivers:

We will examine the historical evolution of buybacks and delve into the three primary reasons why management teams and boards heavily utilize them as a capital allocation tool. By understanding the underlying motivations for buybacks, we can gain insight into their widespread adoption in corporate practices.

- The Detrimental Impact of Poor Buyback Strategies on Ongoing Shareholder Value:

Through a clear and straightforward hypothetical example, we will mathematically demonstrate how poorly executed buyback strategies can erode value for ongoing shareholders. We highlight the specific ways in which these strategies fail to deliver the intended benefits and, instead, result in a negative impact on shareholder returns.

- Exploring Alternative Strategies for Delivering Shareholder Value and Effective Investor Messaging:

We will explore alternative strategies beyond buybacks that have the potential to enhance shareholder value. Additionally, we will discuss how management teams can effectively communicate these alternative approaches to investors. By examining the benefits of these alternative strategies and understanding the importance of clear messaging, we can pave the way for a more comprehensive and value-driven approach to capital allocation.

Popularity of Buybacks

Once perceived as a form of market manipulation, stock buybacks were prohibited in the 1930s. However, a significant shift occurred in their regulatory status when the SEC introduced Rule 10B-18 in 1982 during the Reagan administration. This rule established a Safe Harbor provision, enabling firms to repurchase shares within specific guidelines. This change played a vital role in combating corporate raiders and addressing principle-agent problems associated with excess cash on balance sheets. As proponents of this change, we recognize it as a highly positive development in capital markets, as it enables management to employ buybacks as a means of addressing such issues.

Since their legalization, buybacks have gained immense popularity and have surpassed dividends as the preferred form of corporate payouts. In fact, buybacks reached a remarkable milestone, a record-breaking figure of over 1.1 trillion dollars in 2022.2 Notably, unlike dividends that are more large cap biased, this phenomenon is observed across both large and small-cap companies, with approximately 90% of large caps and 80% of small caps participating in buyback activities in recent years.2

As previously stated, the belief that buybacks are a means of returning value to shareholders is universally accepted. Robert Reich, a former labor secretary and my former economics professor, captures the basis of this belief by stating,3 “Buybacks...force stock prices above their natural level. With fewer shares in circulation, each remaining share is worth more.” This line of thinking, coupled with the substantial volume of buybacks being executed, has drawn political attention. The natural leap is to conclude that buybacks are enriching shareholders and executives at the expense of hard-working Americans. Curiously, Reich's line of thinking overlooks the cost associated with this concentration of shares. While ongoing shareholders now possess a higher portion of earnings for each share they own, the company's cash/equity has been exchanged for this privilege. In the subsequent example presented below, we will clearly demonstrate why the notion that buybacks unconditionally 'return shareholder value' warrants questioning and qualification. However, before delving into this core discussion, it is essential to momentarily detach from the political noise and provide an overarching understanding of why buybacks have become so prevalent in today's corporate landscape.

The Three Primary Reasons Companies do Buybacks Today

Reason 1: A flexible approach to satisfy shareholders and mitigate activist scrutiny

Companies with surplus cash often face pressure from shareholders to allocate capital effectively. While dividends have long been considered a reliable method of returning capital, they possess inherent inflexibility. If a company were to reverse its stance and announce a dividend cut, it would be met with a significant stock price decline. Companies experiencing dividend cuts or eliminations face an average stock price drop of approximately 7% upon announcement.4 Conversely, there is no such market punishment when companies refrain from announcing buybacks or even fail to follow through on previously announced buybacks. Buybacks, in comparison, carry less price risk and afford management greater discretion, making them a flexible approach to appease shareholders and address the issue of excess cash, which could otherwise attract activist attention.

Reason 2: To immunize dilution from Stock-Based Compensation (SBC)

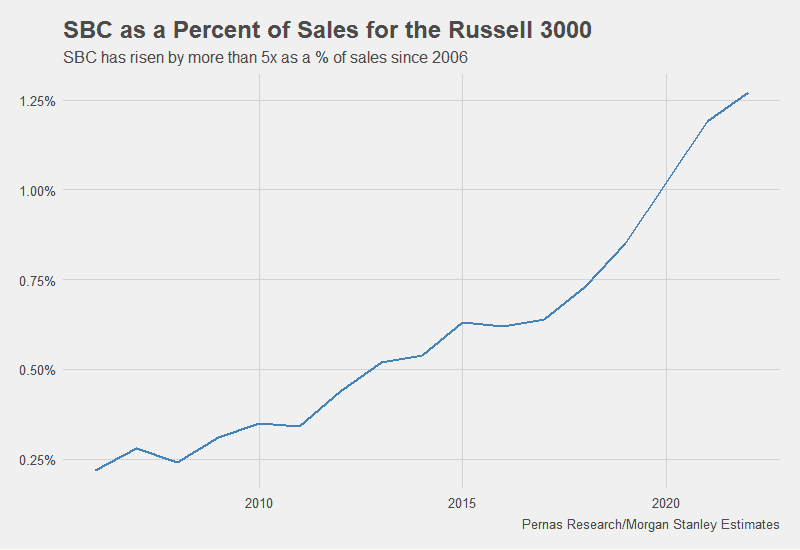

More and more Stock-Based Compensation (SBC), which inherently carries dilutive effects, is increasingly recognized as a means to compensate executives and employees. SBC has experienced significant growth as a percentage of revenue over the years, with factors such as the expanding presence of the technology sector and a decline in cash-flowing companies being cited as contributors.5

Various forms of SBC, including Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs), Performance Stock Units (PSUs), Stock Options, Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs), Restricted Stock, and Restricted Stock Units (RSUs), serve as useful tools for retaining, motivating, and compensating executives and …