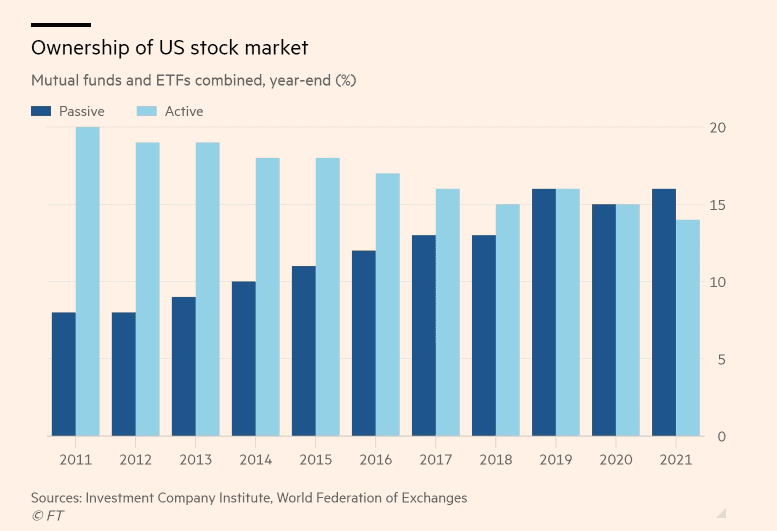

What is corporate governance? How does one discern good corporate governance from bad? Why should an investor even care about governance? Corporate governance is the checks and balances that attempt to enable ethical behavior, proper decision-making, and accountability; Management is accountable to the board, and the board is accountable to shareholders. Good corporate governance incents managers to act as responsible owners of the company, taking a long-term view of the business and threading the tension between using capital for the business versus distributing it back to shareholders. As passive investing has increased and holding periods have decreased, the feedback mechanism for sound corporate governance has diminished, making it all the more important for investors to pay attention to governance. Although there are signals to help an investor determine if a company has good governance, there is no prescriptive list that guarantees the board and management will always act in an owner-oriented capacity.

The causality between good corporate governance and a management team that is owner-oriented is tenuous. For instance, until 2004, Berkshire Hathaway’s corporate governance would now be considered extremely suspect. Most of the board was made up of insiders, and the remaining directors would have violated the current independent director1 listing rules. In addition, Buffett was both the CEO and Chairman of the Board. Although its corporate governance score would have failed the current litmus test, one would be hard-pressed to find a critic that didn’t believe Berkshire Hathaway was – and still is – run in an extremely ethical and shareholder-oriented fashion.

Evaluating Corporate Governance

An investor should first begin assessing corporate governance by first inverting; what characteristics does bad governance have? Bad governance means management and the Board act in a manner opposed to shareholders which generally means pilfering company coffers. Companies without governance guard rails have boards that are staggered and insider-dominated, rampant dilution, high director cash-compensation (>$400k/year), “serendipitous” option grants, poison pills, egregious severance packages, additionality liability insurance policies for directors, and dual-class structures. There is also a severe lack of oversight by audit committees– likely coupled with frequent auditor changes– and significant foresight by compensation committees. Buffett recounted an anecdote where board members who were paid large cash salaries purposefully scuttled proposals to acquire their company at a substantial premium!

Good Corporate Governance Signals

Good governance attempts to have boards that are stewards of the company and who can ask critical questions of management. Although this sounds easy to implement, in practice it is extremely difficult. Boards are social ecosystems by nature and there is an almost gravitational pull towards collegiality. Directors want to continue serving as directors and that is done by maintaining familiarity and not disturbing the waters. Even Buffett, with his prodigious investing experience and ultra rationality, remarked about his experience on boards “too often I was silent when management made proposals that I judged to be counter to shareholder interests.” Sometimes collegiality trumps independence. We list some structural governance mechanics that promote independent behavior. The below information can typically be found in the proxy statement along with shareholder proposals, how management is compensated (although emerging growth companies are exempt from this), ownership structure, who the auditors are, etc.

- The CEO and the Chairman of the Board are not the same individuals. Roughly 60% of boards in the SP 500 have split Chair and CEO roles.

- The Chairman of the Board should also be an independent director per NYSE and Nasdaq listing rules. Roughly 36% of SP 500 boards have an independent chair.

- The entire Board is up for election in a non-staggered fashion. This means the entire slate of board directors can be replaced in one year instead of several. Roughly 60% of SP 500 boards are staggered.

- The majority of the board (>70%) should be independent directors.

- Directors should have significant equity ownership in the company. Their equity ownership should be multiples higher than cash compensation.

- The directors should have a diverse set of experiences. There is no marginal benefit to hiring directors that have the same background as the rest of the board. The board should have a mix of investors and executives.

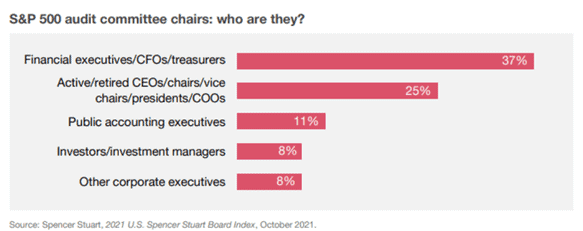

- The Audit Committee Chair has a strong finance background – ideally previously a CFO or accounting executive. A survey of audit committee chairs is shown below.

- There should be a minimum of two independent directors on the Compensation Committee.

Board Committees

There are several committees on a board: There is an audit committee, governance committee, compensation committee, risk committee, nomination committee, etc. The majority have fairly standard charters. For example, an audit committee oversees financial reporting and disclosures. Post Sarbanes Oxley, the audit committee is directly responsible for appointing the company’s auditor and ensuring accurate financial reporting. Prior to Sarbanes, there were directors such as OJ Simpson sitting on the audit committee of Infinity Broadcasting. The members of an audit committee should be completely independent of the auditing company. We will focus on the one with the most discretion: the compensation committee.

A compensation committee is responsible for approving strategies by the CEO, evaluating their performance, and determining the compensation based on those strategies and performance. The committee controls the equity grant size, type, timing, and vesting which gives them a stabilizing power dynamic with the CEO. It is vital that this committee structures compensation to create economic incentives to enable an owner mindset for management. Incentives should not be short-term and cash-based, but long-term oriented and equity-based. The more compensation is equity-based and long-term oriented, the more aligned. A study (Von Taol and Ruenzi, 2014) found that firms with high equity incentives outperformed other firms by 4-10% per year.

Generally, the compensation and metrics a Board arrives at are usually determined by looking at compensation packages in peer companies however, compensation should be more of an absolute determination and metrics should be specific and core to the business which showcases the strategy of the firm. The at-risk percentage of pay should be sizeable versus the fixed portion and …